dcapuano@learningconsultantsgroup.com

sstaunton@learningconsultantsgroup.com

Behaviorism, the psychological theory developed by B. F. Skinner, among others, over several decades, emanates from the common-sense observation that people act in order to either get something they want or avoid something they do not want.

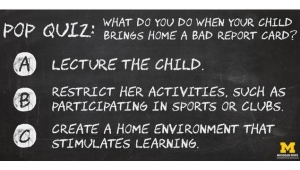

Those who espouse a simplistic view of the theory posit that we should be able to figure out the right mixture of rewards and punishments to entice whatever behavioral outcome we desire. As every parent knows, the complexity and uniqueness of the human mind make life much more fun!

Behaviorism works to a degree with many children. But, it rarely works for very long and rarely pushes students to great heights. Avoiding punishment is not so inspiring. And, in our fairly indulgent suburban Connecticut society, the rewards have to be fairly spectacular to push the unmotivated through school days of drudgery.

Nonetheless, some elements of behaviorism work well. The best time to approach the reward and consequences discussion is not after a disaster. That conversation will be negatively charged and you are likely to focus too much on the punishments.

Having a “kick-off” conversation at the start of the school year or at the start of a new marking period is ideal. The discussion should be approached from the perspective of loving parents attempting to help their child. Presenting a reasonable reward-consequences plan based upon your expectations will be effective and a lesson in how the real world operates.

While behaviorism works to a degree, as I wrote in Motivate Your Son, the far better long-term approach involves shifting your children’s actions through inspiring them within their core motivational pattern.

So, for example, we recently were working with a floundering student at Daniel Hand High School in Madison, CT. His parents had tried every form of behaviorism (reward/punishment) to get him to study. He was both stubborn and uninspired.

After understanding that his motivational pattern focused on being unique – and he was unique in his otherwise high-achieving family – we were able to move him towards feeling special in areas that mattered to him (music) while understanding that areas that didn’t make him feel special (math) were still critical to his overall goal (admission to NYU).